In This Issue

___________________________________________________________________________________

New Poems by Genine Lentine Old Poems by Pat Nolan Olga Zilberbourg Short Shorts Bios

Introducing The Cove

I grew up less than a mile from Kelly’s Cove, the bit of

shoreline at the north end of Ocean Beach in San Francisco. The Cliff House

founded in 1858 and now in its fifth incarnation, is perched just above the

basalt cliff. Its third embodiment, as an eight story Victorian palace built in

1895, survived the 1906 earthquake and fire but was consumed by a raging blaze

the next year.

The cove below is welcoming, with the city behind and the

bold horizon line ahead, stretching as far as one’s imagination can travel. I

had this hallowed place in mind when I conceived The Cove as a gathering place and gallery focused on some of the

issues Northern California writers and artists face, and the creative work that

grows from their interactions with these issues.

Each edition of The

Cove will concentrate on a particular theme. We kick off with Fire, in response to the devastating

fires that roared through the North Bay last fall, destroying many lives,

upsetting so many more, as 9,000 homes and businesses were swallowed and

hundreds of thousands of acres turned to ash. Our hearts go out to all who

suffered and we remain grateful to the first responders.

Creative artists don’t necessarily operate as first

responders, either in terms of immediate response or with the goal of

eliminating the problem at hand. The job of artists is to wrestle with their

own singular vision and to offer the results as honest testimony of their

efforts. That said, much of the writing and the work of the fifteen artists

gathered in this edition of The Cove was

created in direct response to the North Bay fires.

We are very grateful to all the artists and writers who

contributed to Fire. The bio section

offers links to contributors’ websites and to other venues offering their work.

We encourage you to explore this work and to be in contact with the artists

whose work engages you. We also invite your comments as well as your

submissions for our Fall 2018 edition, The

Art of Resistance. Welcome to The

Cove.

Bart Schneider

Editor

Fire Art By fifteen Bay Area artists

Chester Arnold

James Brzezinski

Kristen Garneau

Fire

Oil on linen

30 x 40 inches

Michael Kerbow

Sear

Oil on canvas

12 x 12 inches

Margot Koch

Fire

Oil on wood panel

12 x 12 inches

Linda MacDonald

Greg Martin

Jude Pittman

The Douser

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 40 inches

Bill Russell

Deborah Seidman

Spence Snyder

Natasha Sharpe

Civilian

Pen and ink with digital enhancement

4.5 x 7 inches

Stephanie Thwaites

Tami Sloan Tsark

Keith Wilson

Fire Poems

Poetry on “Fire” from Northern Californian writers.

Two Fathers

Susan Griffin

Firecats

Lisa Summers

What We Packed at 3 A.M.

Katherine Hastings

Sifting Emptiness

Gwynn O’Gara

Drunken Mother

Gwynn O’Gara

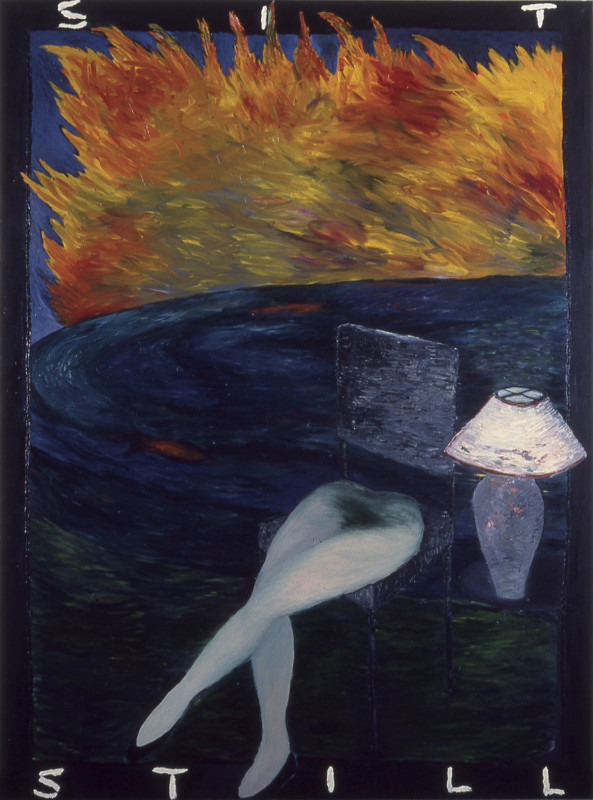

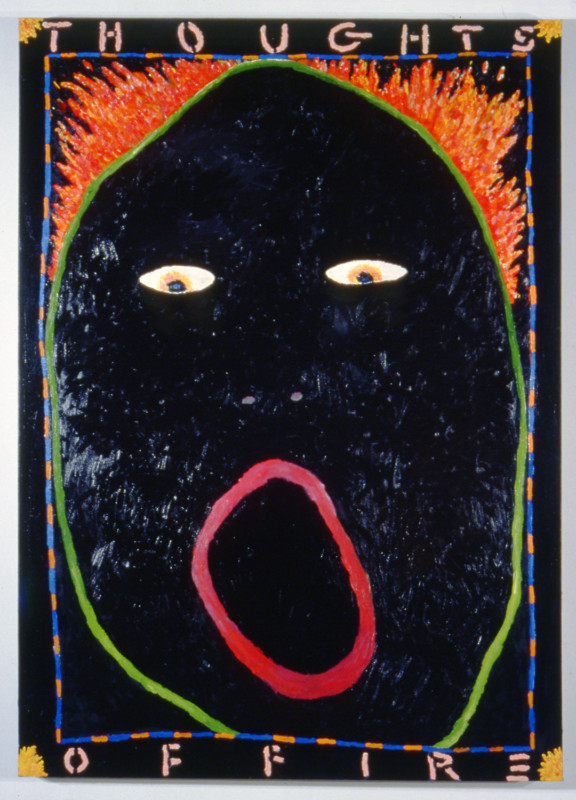

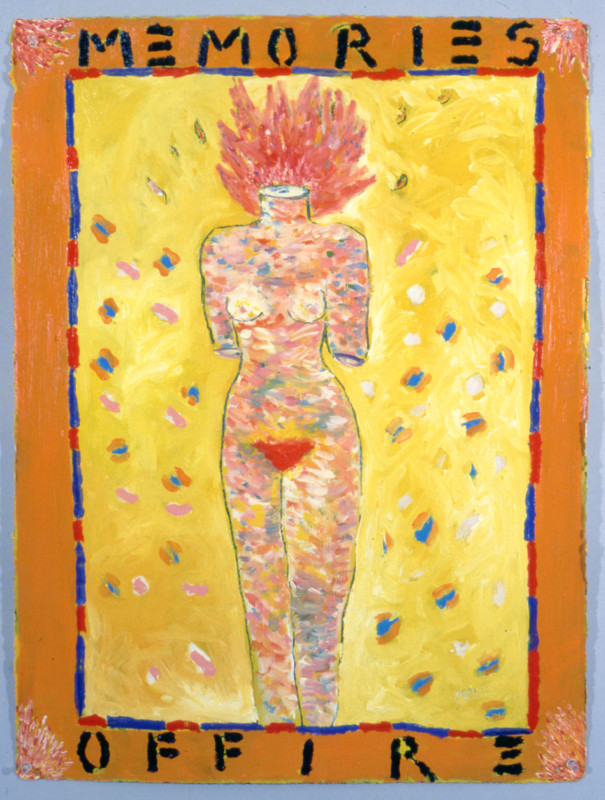

Squeak Carnwath’s Fire Art

In 1982 Squeak Carnwath made an extensive series of fire paintings, including the following images. “I’ve always been phobic about fire,” she says. “I was carried out of a house on fire as a child and I averted a number of studio fires including one involving a pile of sawdust and a hotplate. Immolation has a finality to it.”

Where’s Willoughby?

“Fires have names, too, she learns. Like hurricanes, sort of. Like stars. But not at all like stars. These fires don’t stay put and no one seems to know where they came from and certainly not where they’re going. How do they warrant the dignity of a fucking name?”

A story by Dan Coshnear

I

The little red light on the fucking coffee maker is on but the fucker’s not dripping. Why? FUCK! She curses all the time when she’s alone, and she’s alone almost all the time. The fucking dog rolling in the compost, then hopping on the fucking sofa. The fucking wind tonight, strong enough to blow a box of empty cans and bottles off the deck and scatter them around her yard. Mostly, Sally curses God, and Graham, her ex. She sometimes wonders, has Graham become god-like in her monumental rage? Has God become ex-like?

She called her old friend Willoughby eight times between 10pm and midnight. He’s fucking difficult to reach under any circumstances – no computer, no cell, just a landline which he’d said he only answers when he’s in the rare mood to give money he doesn’t have to people he doesn’t know.

She called because he has called her every Sunday night without fail, ever since he’d been diagnosed with Parkinson’s. That was April. Their weekly chats began at her insistence, because she feared he might be lonely, that he might withdraw from the world; she couldn’t have anticipated how much she’d come to rely on them.

She keeps calling because it happens to be Sunday, October 8th and his home is a wooden cabin on a wooded hillside several miles west of Calistoga.

At a quarter past midnight, she takes a deep breath and calls Graham.

“Where are you?” are his first words. It’s been more than a year since they’ve spoken and the last time she’d vowed, would be the last time. We grieve differently, he’d said. Why can’t you accept that? He was in L.A. then grieving with a chick named Zoe.

“I’m home,” she says.

“It’s three fifteen!”

“Where are you?”

“New York.”

“I shouldn’t have called.”

“Wait.”

“Take a look at the news, Graham. Call me back, if you want. I’m not fucking going to sleep.”

She clicks off the phone and clicks on the TV remote. The fire is vast and spreading rapidly. In fact, there are many fires. She hears the names of neighborhoods, boulevards, streets. The first footage shows Fountain Grove, then Bennet Valley, black swirls with flickering tongues of orange. The camera pans at what appear to be huge white roiling clouds, the entire screen goes white, the sound of crackling, then back to black sky, and flashing emergency lights. She sees maps and diagrams. Coffey Park is burning; the fire leapt over the highway. These winds are called El Diablo, she learns. They are intense, but also familiar, seasonal. It’s a new concept. Fires have names, too, she learns. Like hurricanes, sort of. Like stars. But not at all like stars. These fires don’t stay put and no one seems to know where they came from and certainly not where they’re going. How do they warrant the dignity of a fucking name?

Graham is back, urgent. “Did you talk to Willoughby?”

Willoughby presided over their wedding. And he is their only mutual friend since the divorce. They’d met and fallen in love, fucking fallen in love, in one of Willoughby’s once famous writing workshops. Sally and Graham had had a child, too. A girl.

“No. We always talk on Sunday night!”

“I know.”

“You know?”

“He told me you’ve been transcribing tapes for him, typing up his manuscript. It means a lot to him.”

“He said that?”

“What he said is, talking with you means a lot to him … hey, maybe he got out on time. Or maybe he’s been evacuated.”

“Maybe not, Graham.” A brief silence. It’s as if she can hear the words he needs to suppress.

“I’ll get a flight in the morning,” he says.

“Why? What can you possibly do?”

“I have no idea,” he says. “Call me if you learn anything.”

“Graham.”

“What?”

“Nothing … thank you.”

“Oh,” Graham says, “Willoughby is his pen name.”

“What’s his real name?”

“I never asked. He never told me.”

II

Sally searches the Internet. She consults Nixle and listens to KSRO. She identifies three evacuation centers in Santa Rosa, but she has difficulty getting any answers on the phone. He’s 75 to 80 years old. He might be in a wheelchair. He might have only taken his walker. He’s bald on top. Likes western wear, denim, that sort of thing, but he might be in his pajamas. What kind of fucking pajamas! I’m sorry. Sometimes he goes by Willoughby. He has blue eyes. A slight tremor.

Now she’s driving east on River Road. The tremor was slight three months ago, when she last saw him. When she last saw him, his name was simply Willoughby. Morning light feels dusky, gray-tinged, a mean yellow orb hovering in the haze. The taste of the air reminds her of a smoky fire at the beach, damp wood and seaweed, acrid, something tickling the back of her throat. A long line of cars and trucks come to a full stop near Forestville.

“I’m at SFO, still in the plane,” says Graham.

“I’m sitting in traffic, too.”

“Shit, Sally.”

“Did you know the last story he sent me is called Deus Ex Machina?”

“My Latin is rusty,” he says.

“It means, god from the machine. It means bad plot.”

“Is it any good?”

“It’s awful. I think it was meant to be awful. Fifteen pages of romance and betrayal, a love triangle, real high drama, then it ends suddenly when the man and the two women are swept away by a Tsunami.”

Graham laughs. “That’s life, isn’t it?”

Sally laughs. “Life has a way ruining good stories,” she says. “Bad stories, too, I guess.”

After half a minute of silence, “Sally, you know, I wish — ”

“I have a call coming in,” she says. “Ring me when you get up north.”

Strange, this sudden impulse to weep. It’s been years. A doc at Kaiser had offered her something to “help you get over the hump.” She refused. The expression made her furious. She curses the cars in front of her, then turns up the radio. Twelve fires. Dozens reported dead and many more missing. Zero percent containment. A list of neighborhoods which have been evacuated and others standing by. Breitbart News reported the fire was started by an undocumented immigrant, and now the voice of the sheriff stating there is no evidence to support that claim. But, Sally wonders, what’s to stop the story like these fucking fires from spreading? The fucking mendacity! Highway 101 is closed. Mendocino Avenue is closed north of College. She’d intended to start with the Vet’s Hall by the Fairgrounds, but maybe she should try the Finley Recreation Center first. And soon enough a man with a respirator and an orange flag sends her in that direction, southward down an unpaved road between a pair of dry empty fields.

The last time she’d been to the Finley Center was five years ago, for swim lessons. Gabby was three, in red trunks and a t-shirt, matching red water wings. She was husky and fair, full-cheeked like her father. She was already ill, but there were no indications, nothing that could be seen without a CAT scan. Sally tilts the rearview as if she might suddenly find her girl in the back, dozing in her car-seat. Her chest heaves. She almost sobs, stifles it. She rolls down the window, breathes in burnt air, and quickly rolls it back up.

III

At Finley, the lot is nearly full. By the entrance she sees an ambulance, the flashing yellow lights look pale against the hazy yellow sky. She sees a woman standing on the curb lift her respirator to take a long pull on a cigarette. There is commotion in the doorway, one man flailing, shouts, “Todos!” as another tries to console him. Once inside, she sees a line, mostly elderly, or women with small children. The faces are white or brown, anxious or bored, or both. Many eyes are trained on small screens in the palms of hands. At the head of the line, a man is taking information, jotting on a clipboard. She suspects she will not be permitted to enter. Who can she ask? She sees a man in a FEMA sweatshirt, a man and a woman with Red Cross badges. Each is engaged, answering questions, enunciating every syllable. She understands, they mean to project a sense of calm and order, but the slow, deliberate mannered speech has always produced the opposite effect in her. Not always. She finds a space on the end of a wooden bench, sits, breathes. Occasionally one of double doors swings open and she hears the low roar of many conversations, glimpses long rows of cots occupied by bodies and backpacks. When the door closes, nearby voices become distinguishable.

“I guessed something was wrong because my dog was sniffing and sneezing. And, of course, the wind.”

“Animals know before we do.”

“They do!”

“We saw the flames coming over the hillside. Jack, my husband, put a few things in the SUV and pushed us all out the door.”

“We were told to evacuate by the Fire Department.”

“We weren’t told anything.”

“The kids wouldn’t leave without the cat. It was terrifying. Tuxedo hid behind some boxes in the garage.”

“I tried to rescue the old man at the end of the cul de sac. I banged on his door, but he wouldn’t answer. God help him.”

Sally is moved to do something, anything. She interrupts a woman speaking to one of the Red Cross workers. “I’m looking for someone,” she says. “Excuse me, I’m looking for someone.”

The Red Cross worker points to the back of a long line leading to another Red Cross worker. “You can give her the name and she’ll check the list.”

“What if I don’t have a name?” Sally says. “Can I go in? Can I look?”

“I’m sorry,” says the Red Cross worker, “but I can’t have two conversations at once.” She points again to the back of the line.

Sally pulls her phone out of her back pocket. “I’m on the bridge,” says Graham. “Traffic is moving now, but who knows?”

“Oh.”

“Any news?”

“Nothing.”

“I think I heard Sutter had to send its patients elsewhere. Maybe Kaiser, too. The thought of going into a hospital again … Sally, you there?”

Sally’s mind is playing tricks. There are two Graham’s speaking, like those before and after photos you see in magazines; the big fellow with the big red beard and the big laugh, the author of half-baked sci-fi stories and time machines, the super-kind critic, the generous man she fell in love with, and the other, the after, the clean-shaven one with the gym bag and the vacant eyes, always on the move, only able to speak in platitudes.

Graham says, “I’ll find out what I can and call you.”

She puts the phone back in her pocket and sees that the nearest Red Cross is turned, looking the other way. The door swings open and she bolts through. She scans the room. She was good at this, so many games of Where’s Waldo. Where’s Willoughby, or whatever his name is? She looks for a white Stetson, a bald head, a frail man on a cot. She looks for a deep red aura. She is surprised by a sonorous voice, much like her dear friend’s, but it is an elderly volunteer announcing the delivery of coffee and donuts.

IV

On her way now to the Vet’s Hall, but why? This venture feels as hopeless as was the search for an oncologist with a new opinion. The search for solace in so many glasses of Cabernet. Though traffic is slow her mind is racing ahead. What was Graham doing in New York? Why does it matter? What will she say to him? How will she be with him? What will she ever do without Willoughby? Yes, people grieve differently. Of course, they fucking do. She just couldn’t hear it from the man she’d chosen to share her life’s path; the man who fled when she needed him most. Willoughby could say it. He said it all the time. Sunday evenings she’d unburden herself, starting with something like the fucking coffee maker or the foul-smelling dog, or the horrors in the daily news, but quickly, and almost unwittingly, on to deeper stuff, her reluctance to go back to work in a classroom since Gabby’s death, her absolute terror at the idea of dating, her sometimes crushing loneliness.

In fact, Willoughby said very little on the phone. He’d pepper in a few questions and he’d listen. Occasionally he’d offer a quote from something he’d been reading; Yeats, Rilke, lately he’d been immersed in the biography of the Dalai Lama. By Wednesday or Thursday, she’d find a cassette in her mailbox with his newest story … Prince Bradford, and the lovely Camilla, paddle out for the first of their board-sailing lessons, as Lady Enid watches through binoculars from behind a divi divi tree, when from nowhere a fifteen-foot wall of water arrives to wash away all their untapped nights and days …

“I think I can be there in an hour,” Graham says.

“Where?”

“Wherever you’ll be.”

“I’m on my way to the Vet’s Hall. Do you remember where that is?”

“By the Fairgrounds,” he says. “Oh, God,” he says, “Do you remember the petting zoo?”

When Sally remembers her daughter, she tends to see her in her later stages, listless and hairless, in a bed or at the treatment center receiving intravenous chemo. She remembers the mouth sores and poor appetite – she remembers holding out a spoonful of soup or Jello and waiting with a smile pasted on her face. Why this should be the case, she has no idea. Yes, she remembers the petting zoo. Gabby was was robust then, and willful, intent on straddling a potbelly pig. A miniature goat was equally intent on eating the ribbon in Gabby’s hair. She had a fit. “Hey,” she says, “I’m coming to a detour, I’d better pay attention.”

She turns up the radio and learns of more neighborhoods being evacuated and a new list of refuge centers. Thousands of homes destroyed, tens of thousands of acres, vineyards and woodland, so much fuel after five years of drought. Tubbs, Nuns, Redwood Valley, Atlas, Cherokee, once the names of communities; now, and perhaps long into the future, will be remembered as the names of fires, and the burnt topography of chimneys and chasses and the charred black trunks of trees. Those who need not be out, she’s told, should stay indoors with windows closed. And what about these crazy winds, calm for now, but El Diablo is expected to dance again tonight.

At the entrance to the Fairgrounds is Grace Pavilion, a large hall with a tall ceiling, often used for banquets or exhibits, now lined with rows of cots. To the left is a station for volunteers, beside it a large table with boxes upon boxes of chips and granola bars, Gatorade and bottled water. She steps back to avoid three small boys racing past, kicking a tennis ball. Other than the children, most of those in motion are wearing name tags, either Red Cross volunteers, or nurses or social workers. Here are people of all ages and colors, snacking or sleeping, or doting on the ubiquitous smart phones. She sees an old woman sitting, massaging her bare feet. An attendant arrives with a wheelchair and pushes the woman down a long aisle to an open door in the back where a sign says Medical Personnel Only. Sally follows looking purposeful, like she knows exactly where she’s going; surreptitiously she scans the rows of nylon and aluminum beds.

As they exit Grace Pavilion, she passes a volunteer, possibly a nurse, seated at a table.

“Wait.”

Sally pretends not to hear.

“Wait,” louder this time. “Where’s your mask?”

“Oh, where did I put the damn thing?”

The nurse reaches in her pocket. She hands Sally a folded white rectangle with elastic ear loops. “Try not to lose it,” she says.

She paces forward, one dread step after another. The sight of gurneys and bags of saline, the smell of iodine, these are the accoutrements of her worst nightmares. Try not to lose it, becomes her mantra.

Here again, this small ad hoc city is divided into communities, on one side of the building people are being treated for burns; on the other, smoke inhalation. Thirty paces ahead, in a bed by the rear wall of the facility, she sees him. As she gets nearer, she sees he is attached to an IV, and a cardiac monitor. He’s taking oxygen through a tube in his nose. His eyes are closed, and he appears to be sleeping.

“Willoughby,” she whispers.

Slowly a smile comes over his face. “No one here knows me by that name.” He’s hoarse. When his eyes open they are red and swollen.

Her eyes swell with tears.

“How did you get in here?” he says.

She’s unable to find her voice.

“They won’t let you stay,” he says. “But I’m sure happy to see you.”

She swallows. “I’ll stay until they kick me out,” she manages.

His lids sink to half-mast.

“How are you feeling?” she says.

“I’m not in pain,” he says. “I feel lucky to be among the living.”

“And did you lose your house?”

“Oh yes, everything. I’d tried to save a few books and papers. Foolish me.” He sets one trembling hand on hers. “I feel lucky,” he says again.

“Graham is on his way,” Sally says.

“I am twice blessed.”

A doctor is coming toward them, pausing briefly at each bed, checking vitals, asking “How ya doing?”

“We better get to work quickly,” Willoughby says. “I once knew this woman -”

“Wait,” Sally says, “you have a story? It’s only Monday.”

“It’s only Monday?” he says. “Well, then you’ll forgive me because this is a very short one.”

“You knew a woman?” Sally says.

“Her house was on fire. Blazing, ready to collapse. She was out somewhere, say the garden. No, not the garden, she’d have noticed. She was at the store, running an errand.”

“Should I be writing this down?”

A long pause. He seems to have faded out.

“Willoughby?”

“She ran into the burning house to save her child.”

“Oh.”

“The house fell down around them. Neither of them made it out.”

“Oh God. That’s awful.”

“But,” he says, “something of a miracle.” He smiles again. His eyes are closed. “The child was unharmed.”

“I’m afraid I don’t get it,” she says.

Again, he appears to have nodded off. And now the doctor is at his bedside.

“Willoughby,” Sally says.

The doctor looks at Willoughby, then at Sally, “This man needs to rest.”

“He’s my friend. I’m here because –”

“You’ll have to visit another time.” And with that a nurse approaches and Sally is led quickly out of the hall.

V

Try not to lose it, she tells herself, walking back through the Grace Pavilion. She dodges a small army of volunteers, arms loaded with bags and boxes. All this urgency. All this energy. Is it love? Where do people get the strength? She’s exhausted, hungry; she hasn’t eaten all day. She wants a big tall beer. She feels bewildered. Wait, she says, and stops to rest on the edge of a vacant cot. Wait. I think I get it. She sees in her mind a ceramic urn, with ashes in it. The child is already dead!

When she steps out into the open air, she sees to the east a spectacular show of orange and pink and magenta on the bellies of the clouds, to the west a fiery red sun low on the horizon. She’d thought she’d used all her prayers, but maybe she’ll try again. One for rain. One for Willoughby, of course. How many do you get? One for everyone.

Graham is coming toward her. He’s big as ever and he’s wearing that red beard again.

“Oh Sally,” he says. He wraps his arms around her. It feels like a before hug. “They moved some patients down to Kaiser in San Rafael. I think we should try there,” he says, almost breathless.

“He’s here!”

“You saw him?”

“Briefly.” She points toward the medical facility. “They won’t let you in, Graham. Not now, anyway.”

“Is he okay?”

“He was in and out, you know, but he’s there. He’s still in there,” Sally wipes her eyes.

“Oh,” Graham sighs, “I’m so glad to hear that,” he says. “I’ll see him. Maybe tomorrow, or the next day. Whenever I can. I’ll get a room down on Santa Rosa Avenue.”

“Could be difficult,” Sally says, “under the circumstances.” She pauses. How exactly does she phrase her question? And how without the tone giving her away? “You don’t need to hurry back to New York?”

“No,” he says, “I think I’ve had enough hurrying. Besides, there’s nothing there for me.”

“Oh?” she says.

“I saw some old college friends, slept on their sofas. Pretty much just got in the way of their busy lives.”

“Oh.”

“Remember how all my stories involved time machines? Remember Willoughby said, ‘what’s wrong with now?’” He laughs. “I guess I don’t believe in time travel anymore.”

“Maybe I do,” Sally says.

Graham looks puzzled.

“My house smells like compost. It’s because of the fucking dog.”

“Oh”

“And we’ll have to go out for coffee because the fucking drip thing is broken.”

He smiles the smile she remembers best.

“Hi Graham,” she says.

- Satellite image of California Fires 2017

Five Poems by Genine Lentine

AMERICA’S MOST WANTED

SLOPE

LETTER TO GRAVITY

I TOLD YOU A STORY

but what Carp said

MY FATHER

Seven Poems by Pat Nolan

BACK TO WHERE I STARTED FROM

LE RAYON BLANC

BIG BOSS MAN

OXYGEN

THE BACK OF THE SURREAL BOX

IN MEMORY OF TED BERRIGAN

OAKLAND 1970

Olga Zilberbourg

Four short shorts

A Wish

Evasion

Graduate School

Her Turn

- Satellite image of California on Fire – 2017

In This Issue

Biographies

Chester Arnold

(Paintings: “Fire in the Hole,” “From Childhood’s Hour,” “Hard Rain”) is a California born, European raised painter whose work on canvas is a bridge between the craftsmanship of past masters and the turbulent concerns of our moment. His paintings have been widely collected and exhibited. “Borderline,” a current exhibition of his recent paintings, closes May 5 th at Catherine Clark Gallery in San Francisco. Arnold has taught painting and drawing for many years at the College of Marin.

ChesterArnold.comJames Brzezinski

(Paintings: “Wading In” “Hearth” “Wall of Fire”) is a retired art professor, artist, musician, and writer, who divides his time between studios in Pacifica and Mariposa, CA. His work has been included more than 150 solo and group shows in the United States and abroad, and is included in public, private, and corporate collections. He has published many articles, mostly for Artweek.

JameyBrzezinski.comSqueak Carnwath

(“Fire Art”) draws upon the philosophical and mundane experiences of daily life in her paintings and prints, which can be identified by lush fields of color combined by text, patterns, and identifiable images. Her work is exhibited widely in the United States and internationally and is in the collections of many major institutions. Carnwath has received numerous awards including two individual artist fellowships from the NEA and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

SqueakCarnwath.comKristen Garneau

(Painting: “Fire”) is a Northern California painter. With children out of the house and parents gone, she is struck with the desire to slow down time and to find a point of stillness. She builds and sketches on the canvas, taking away what is unnecessary, paring down the visual language. Her influences include the landscapes of Gottardo Piazzoni as well as the work of Rothko and Milton Avery. Seager/Gray Gallery in Mill Valley represents her work. She will have a one-person show in November.

KristenGarneau.comSusan Griffin

(Poem: “Two Fathers”) is a philosopher, essayist, and playwright. Her books include Women and Nature and Chorus of Stones: The Private Life of War. She received the Fred Cody Award for Literary Lifetime Achievement from the Bay Area Book Reviewers, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and an honorary doctorate from the Graduate Theological Union. Susan contributed an essay, “If the Clothes Fit” to Viola Frey, Women and Men, published by Kelly’s Cove Press.

SusanGriffin.comKatherine Hastings

(Poem: “What We Packed at 3 AM.”) is the author of 3 books of poems, most recently Shakespeare & Stein Walk Into a Bar. She is the editor of several anthologies, including Know Me Here – An Anthology of Poetry by Women (WordTemple Press, 2017) and What the Redwoods Know – Poems from California State Parks (2011). Poet laureate emerita of Sonoma County, Hastings founded and hosted the WordTemple Poetry Series and WordTemple on KRCB FM for over a decade. Her archived programs can be found at radio.kcrb.org.

KCRB.orgMichael Kerbow

(Painting: “Sear”) is a San Francisco-based artist who works in a variety of media including painting, drawing, assemblage, and digitally-manipulated photography. He received his MFA from Pratt Institute in New York. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally and has appeared in multiple publications.

MichaelKerbow.comMargot Koch

(Painting: “Fire”) grew up in Hollywood, California but has lived most of her life in Marin County. She has worked as a prop fabricator, set painter, book illustrator, art teacher and oil painter. She also had a stint as a back-up singer in San Francisco. Her formal art education has been primarily the study of Japanese kanji and oil painting but her primary teacher is nature.

BreakingEggStudio.comGenine Lentine

(“Five Poems”) is the author of Archaeopteryx (Artifact, 2016), Poses: An Essay Drawn from the Model (Kelly’s Cove Press, 2012), Mr. Worthington’s Beautiful Experiments on Splashes (New Michigan Press, 2010) and co-author with Stanley Kunitz of The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden (W.W. Norton, 2005) Recent work appears in Lion’s Roar, and in Renga for Obama. She teaches privately and at San Francisco Art Institute.

GenineLentine.comLinda MacDonald

(Painting: “Message Within,” “Antipodes”) is a native Californian, has lived in rural Mendocino County for many years. Her current concerns are the California redwood trees: their conservation, appreciation, knowledge, discovery, and stewardship. She hopes to increase awareness of their plight through her artwork. MacDonald taught high school for many years. Her artwork is in the collection of the White House, the city of San Francisco, the Museum of Art and Design (MAD) in NYC, and the University of Nebraska International Quilt Study Center & Museum.

LindaMacDonald.comGreg Martin

(Paintings: “Consumed by Fire” “Incarnate”) “Realism not imbued with an artist’s imagination is, at least for me, a lifeless form of art. I strive for realism within an offbeat composition of landscape and culture. Realistic scenes with just enough out of place to make the viewer pause. Whimsy and darkness, metamorphosis and solitude are common themes in my work. I live in Marin County with my six-year-old daughter. “

GRMartin.comPat Nolan

(“Seven Poems”) lives in Monte Rio along the Russian River. His poems, prose, and translations have appeared in literary magazines and anthologies in the US and Canada as well as in Europe and Asia. He is the author of over a dozen books of poetry and three novels. He maintains the poetry blog Parole for the New Black Bart Poetry Society, and is co-founder of Nualláin House, Publishers. His serial fiction, Ode To Sunset, is available for perusal at odetosunset.com.

OdeToSunset.comGwynn O’Gara

(“Poems: Sifting Emptiness” and “The Drunken Mother”) Gwynn’s books include Snake Woman Poems and the chapbooks Fixer-Upper, Winter at Green Haven, and Sea Cradles. A long-time teacher with California Poets in the Schools, she served as Sonoma County Poet Laureate 2010 through 2011.

Jude Pittman

(Painting: “The Douser”) Jude Pittman makes drawings, paintings, digital art, videos and mosaics at her California studios in Pacifica (Bay Area) and Mariposa (Sierras.) Most recently her focus is on video drawings.

JudePittmanArt.comTheresa Rife

(Web Designer) has been working with Kelly’s Cove Press as a website administrator, designer, editorial assistant, and general fixer since 2011. Theresa also works as an audio engineer and enjoys singing to dive bar audiences in her off-hours. She lives in Oakland.

TheresaRife.comBill Russell

(Drawing, paintings: “Fire Car,” “House on Fire Sketch,” “Fire Scape”) is a painter, illustrator and visual journalist. He earned his degree from Parsons School of Design in New York. Bill was an adjunct professor of Illustration at California College of the Arts and a staff artist at the San Francisco Chronicle. He recently completed an artist residency at Recology in San Francisco and at Kala Art Institute in Berkeley. He is an expat Canadian and lives with his wife and dog in San Rafael in a restored Eichler home.

BillRussellFineArt.comBart Schneider

Deborah Seidman

(Painting: “After the Fire”) was born in Boston and went to Vesper George School of Art. She studied painting at College of Marin in the 1980’s and is again studying at College of Marin, Indian Valley campus. She has participated in Marin Open Studios for years, selling over fifty paintings. Along with painting, her work includes drawings, and mixed media watercolors.

Natasha Sharpe

(Pen and ink with digital enhancement: “Cilvilian”) is an illustrator, animator, and storyteller who amuses herself by projecting personalities onto inanimate objects and distilling the chaos of the real world into an easily digestible biscuit. She was born and raised in San Rafael, California, and graduated from the RISD Film/Animation/Video department in 2017.

NSharpe.myportfolio.comSpence Snyder

(Paintings: “Followers,” “The Edge of Midnight”) is a Bay Area native who grew up in Novato and who currently lives and works in Mill Valley. He received a degree in illustration from Academy of Art University in San Francisco and a degree in Fine Art from the University of San Francisco. His most recent studies at College of Marin and City College of San Francisco have focused on a deeper understanding of the human figure working with live models as a foundation for both drawing and painting. He has been exhibiting work since 2013. Instagram – ArtOfSpence

SpenceSnyder.comLisa Summers

(Poem: “Firecats”) is the author of two collections of poetry – Star Thistle and Other Poems (FMRL, 2012) and Ogygia (FRML, 2014). Her latest book, The Green Tara – is a wine country caper set in Northern California (FMRL, 2017). She is the co- founder of the Sonoma Writers’ Workshop, which hosts a popular series of poetry readings at BUMP Wine Cellars in Sonoma.

Bohemian.comStephanie Thwaites

(Paintings: “Of Desire,” “Scar”) holds a BFA from Yale University, where she studied painting, graphic design and photography. She did further graduate study in design in Switzerland. After a 20-year career as a graphic designer, creative director, and brand manager, Stephanie returned to her fine arts background full time in 2009. She has exhibited in several solo and group shows and in November has an upcoming solo show at the Belvedere-Tiburon Library.

StephanieThwaites.comTami Sloan Tsark

(Paintings: “Where There’s Smoke” and “Safe Harbor”) is a San Francisco painter who also works in mixed media and sculpture. Her work has been exhibited in Los Angeles, Sonoma County and San Francisco, and has been published in Artweek. She received her BA from UCLA in Film/TV, where she specialized in animation.

TsarkArt.wordpress.comKeith Wilson

(Paintings: “Firedance,” “It Will Be Green Again”) graduated from UC Berkeley with a BA Environmental Design (minor in etching) and a Master Degree in Architecture, having maintained an architectural practice until 2001 and an active painting practice since the 1970s. He maintains studios in San Rafael and on the Sonoma Coast.

KeithWilsonArt.comOlga Zilberbourg

(“Four Short Shorts”) is a bilingual author who grew up in Russia and moved to the United States at the age of seventeen. Her third Russian-language book of short stories was published in Moscow-based Vremya Press in 2016. In English, her fiction has been featured in Confrontation, World Literature Today, Tin House’s The Open Bar, Narrative, Outpost19’s Golden State 2017, as well as other print and online publications. Her short fiction won the 2017 San Francisco’s Litquake Writing Contest and the 2016 Willesden Herald International Short Story Prize. She co-hosts the weekly San Francisco Writers Workshop.

Zilberbourg.com